Threat Monitors Part 1: How to sense the rising waters

How do you track the untrackable?

Anyone who deals with low probability, high impact risks knows this challenge well. Unfortunately, analyzing these risks is difficult. The necessary information for this analysis is often out of reach - buried in dense reports or dated and no longer relevant. We need a better way of predicting the unpredictable.

Take, for example, a business in Greece and the uncertainty of the country's place in the eurozone. Right now that seems like an absolute fringe event. No chance whatsoever Greece will leave. Then again, in 2006, there was little suspicion that the US housing market would crash. In 2010, no one would have thought that there would be a referendum on the UK’s membership in the EU (or that it would lose). And it was only five years ago that Greece voted in a referendum against the bailout deal.

Since improbabilities have proven not to be impossible, we need to prepare for them. The problem is that, unlike an election with plenty of polling, or a high-profile situation with numerous historical parallels, we don’t have much data to work with. This can especially be true for a risk where the drivers are wide-ranging. How should an analyst measure the chance of a return to the drachma if the causes may come from domestic politics, the banking system, macroeconomics, Brussels drama, or even how the pandemic shapes global tourism?

There is one method that can help: threat monitors.

Over the course of three posts, we’re going to walk you through a new approach for these risks..

As always, if you want to talk further about how to best use these tools for your organization’s needs, and turn the theory into reality, we’re here to help.

Targeting a monitor

Threat monitors are best suited for those risks that are concrete enough to know if they come true, but broad enough not to know in advance where the signs will come from.

Let’s take two issues that wouldn’t work for this system.

First is the US presidential election during the general election. There’s enough polling from now until the vote that to build a monitor would be overkill.

Second is what the future of work looks like. There are so many possibilities that a single monitor would be overwhelmed trying to handle it all. You would be trying to funnel everything about productivity, offices, and technology into one datapoint. You could built monitors for subsets of the future of work (like the threat of remote working to commercial real estate), but not for the entirety of it.

Instead, we want to isolate the threats that we are concerned about that are 1) concrete and falsifiable and 2) can’t be tackled in a more targeted approach, like the Greek exit from the euro above.

In this series, we’re going to show the utility of threat monitors by tracking a risk that should be concerning to diplomats and US government officials: will China supplant the United States as the soft power leader in the world.

China's dominance as the soft power leader would alter the global system, is not going to happen immediately but may in the future, and is a topic with so many factors that traditional analysis may not be able to incorporate everything effectively.

Building a monitor

An effective monitoring system tracks the factors that shape and drive the threat.

Greece’s chances of leaving the euro is unmeasurable. But it is more likely to leave if the economy goes down, if the EU imposes fiscal restrictions in new treaties, and if tourism is permanently damaged by COVID-19. We can measure all of those things and, by adding together the effects, find how the overall probability has moved.

Once we know what threat we're trying to measure, we need to know its components, how to measure these components, and how to combine these components to create an overall score.

We’ll be doing this in a five-part process to build our China-US soft power threat monitor.

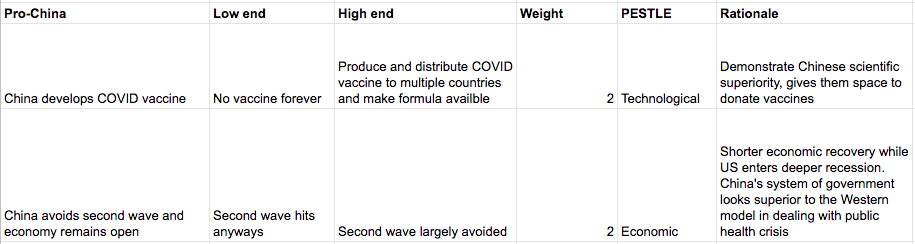

Find five factors that would increase China’s soft power relative to the US and five that would decrease it. The number must be high enough to cover the many factors but not so high you can no longer manage them. Give a rationale for why each is included, and categorize it as being a factor from politics, economics, society, technology, law, or the environment (PESTLE).

Identify the realistic low and high points of these factors. This helps us set expectations of how much volatility will be in this particular metric and keep us from over- or under-estimating the events we see in the news.

Weight the variables. Not all factors are created equally. A drop in tourism will matter to Greece, but not as much as a new EU treaty that outlaws deficits.

Measure each variable according to where you think it falls on the spectrum between the low and high points.

Add it all up.

Below is how we did this for the first two pro-China factors, with simple weightings between 1 and 3.

The overall China monitor looks like this.

What a monitor tells us

Okay, we’ve built our monitor, and it tells us that the threat of China overtaking the United States in soft power is at a 9.5. What does that mean?

By itself, nothing.

This number only gives us a present measurement of the situation, according to our newly-created monitoring system.

The value comes after we run the system for a few weeks, or months, or years. If that 9.5 starts to rise, we might look into the threat more. If one component is trending downwards while the others move up, we can commission deeper research. If the overall situation appears to be getting worse while the monitor is static, we may have to revisit our factors.

These monitors synthesize disparate types of information into a single digestible data point, structure our own thinking, and show us where we need more analysis. Like wargames, these monitors help us interrogate issues in ways that standard meetings and reports might miss.

And there’s more. Now that we have a tracker on the pulse of this issue, we can build on that foundation with two additional approaches that we’ll be talking about in the second and third posts of this series: forecasting and simulating whether this threat comes true.