Threat Monitor Part 3: Simulating threats

Threat monitors are great for tracking low-probability / high-impact dangers that can creep up on an organization as discussed in Part 1 of this series. In Part 2, we showed how to extend the idea into a forecasting model that challenges a team to think more critically about the future.

There is one question that you might have about forecasting. How do we know if we’re right?

All forecasting is associated with uncertainty. Some future events we can be pretty confident about, for example what the US population will be in 2025. Other events, however, like tho the US President will be in 2025, are much harder to predict. A good forecast will capture and communicate that crucial axis of thinking.

Threat monitors are no different. In Parts 1 and 2 we used threat monitors to produce a single data point that we could track over time as it rises and falls. By adding uncertainty measurements to our scores and weighting, we can use Monte Carlo simulation to generate a distribution of normal options.

Adding Monte Carlo to the monitor

If we are not sure about what the future will look like, we can get a better sense by simulating 10,000 futures.

The Monte Carlo method uses both our estimated scores, weights, and uncertainties for each. The below shows how the forecasting model used in Part 2 has been built out for this purpose.

We then simulate, as we do in the Influence Bargaining model, what the potential futures might be. Each simulation that we run finds a total based on the estimated scores, weights, and uncertainty measures that we give to each. (If you’re interested in the math, the scores/weights are the mean of a normal distribution, the uncertainty is the standard deviation, and each simulation randomly generates a weighted score based on those distributions).

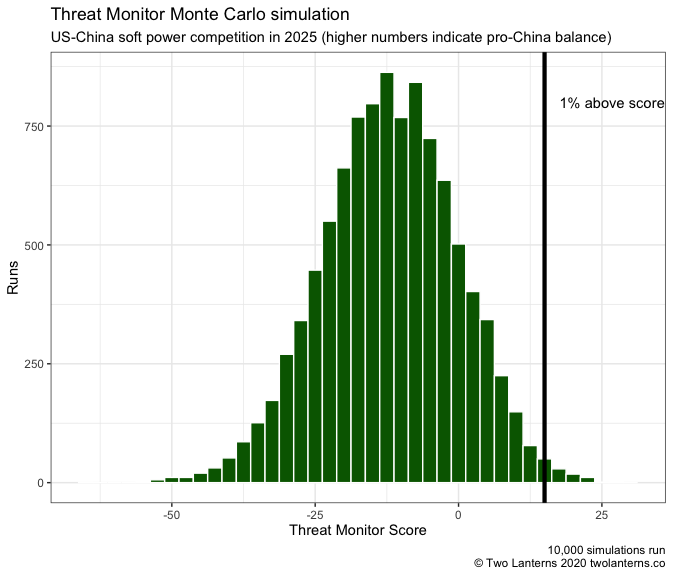

By running 10,000 simulations, we produce a bell curve of the possible distribution of forecast threats.

Why add uncertainty?

You might be asking yourself why this is necessary. Threat monitors are inherently artificial. We pick a handful of factors to track when, of course, the situation could be impacted by millions of events. The resulting number is not predictive in itself, but is most useful at showing us a rising or falling threat. Why complicate things by including uncertainty measurements?

There are three main benefits to this approach.

First, it forces us to confront one of the most important elements in a forecast.

Uncertainty is often more dangerous when it is underreported. The lesson of the 2016 election and Brexit were not that analysts were incorrect to forecast a Clinton or Remain win. Clinton was ahead in the polls and there was a logic to late-deciders breaking for Remain. But the mistake came with the level of certainty commentators gave those predictions. Clinton was favored - but by no means a shoe in. Remain had a strong argument - but not an unassailable lead.

When we make a forecast in a threat monitor, it is critical for an organization to know what factors are well known and what are gaps in their knowledge. If the State Department were running the US-China monitor, they could be pretty sure about how China’s influence is faring in Hong Kong. They may be much less sure about Europe’s reactions. That tells them that any monitor change based on news from Brussels or Berlin may not be as consequential as it seems.

Second, forcing uncertainty to the surfaces helps direct further research.

If a team gathers for a monitor update and admits that they don’t have a clear picture of European attitudes towards China, that tells the boss where the next research push should be.

Debates around uncertainty can also lead to productive conversations and flush out the overconfident. If an analyst argues that uncertainty should be 0.1 rather than 2 (ie, the score or weighting is pretty much known), that could trigger difficult questions about his assumptions. Those questions would probably go unasked in a standard seminar session. The monitor process allows tougher discussions than office etiquette usually allows.

Third, running simulations allows us to see what is the probability that the situation gets above a certain threshold.

Perhaps with the US-China soft power competition monitor, we don’t care about any score below a 15. We’ve looked hard at what scenarios could get us there and have concluded that Chinese soft power will only be a challenge to US interests if it’s above that level. That is the essence of the threat that we want to track.

By running thousands of simulations, we can see how probable we are to get to that threshold in the time horizon of the monitor. We can get there either by the scores trending in that direction or uncertainty changing. In the above histogram with blue columns, we find that in 27% of simulations, we go past that 15 threshold.

If we grow more confident in our scores and weightings - perhaps because we get a cache of intelligence or have researched the situation further - we could drop that to 20% by shrinking the width of the bell curve. That is seen in the red chart below. Or maybe the situation changes and we see the curve move away from that threshold, as in the green chart, where the probability of going over 15 happens in only 1% of simulations.

Conclusion to threat monitors: Why use them?

In these three posts, we’ve gone over the process and purpose of building threat monitors for the present, the medium-term, and with uncertainty added. But it’s important to take a step back and ask why an organization should take the time to spend time on any of this.

Political risk measures the unmeasurable. Who is to say, truly, what the chances are that China invades Taiwan in the next 10 years? We have no data set for this. No mass of historical examples to parse through. Much of political risk boils down to a set of n = 1 analysis.

What’s more, it’s built on analysis that is often highly subjective. What is China’s soft power in the world? Experts could compellingly argue for it being high, low, or anywhere in between.

Yet teams still need to make decisions. They must be able to talk about these issues and come to a conclusion to guide their work product. Ignoring them and hoping that the threats never arrive is the best way to be caught by surprise (and if you’re reading a post on political risk methodology, you must already agree).

Threat monitors are an organizational tactic as much as a measure of the political situation. They force conversation, highlight what the team should be watching for, and outlast changes in personnel. Rather than reinventing the wheel every time a new employee shows up, threat monitors ensure that institutional knowledge is retained and directed towards what the organization needs to know.

There are many ways to track political risks, but threat monitors are one of the more time- and cost-effective. For more information on how to design your own, or help calibrating them, get in touch.